Your Book Isn’t Just Fat. It’s Morbidly Obese.

Word Count Makes Your Book Fat. How to Cut It Without Killing Your Voice.

Word Count never asks what your sentences do. Only how many there are.

Words aren’t value. Pressure is Value.

A sentence earns its calories when it does at least one of these:

changes the situation

tightens a relationship

forces a choice

adds danger

makes the reader revise what they assumed

creates a question that needs answering

Everything else just fattens your book.

And before you yell “atmosphere”—

“Atmosphere” is the most abused alibi in writing.

But real atmosphere isn’t mood and vibes. It’s threat distribution. It’s Pressure.

It’s the sense that if someone touches the wrong doorknob, something irreversible happens.

If your “atmosphere” can be cut without changing anything, it wasn’t doing anything.

Atmosphere that matters does at least one job:

raises stakes

reveals power

foreshadows consequence

forces behavior

The reader don’t give a shit about your well-described corridor.

They remember what the hallway did to someone.

Below is three exhibits from existing books. I’ve changed them a bit to make them unidentifiable.

Exhibit A: the “I walked” economy

“The two ladies, Mildred and Petunia, walked really fast down the narrow street, their shoes making a shuffling sound on the ground until they finally got to the door they had been walking towards for all afternoon. It was the right door, so they stopped. Instead of knocking like a normal person would do, Mildred reached out her hand and opened the door very, very slowly, making sure not to make a single sound as she slipped inside the building.

Petunia followed right behind her, also slipping inside because she didn’t want to be left out in the lane by herself. Once they were both inside, they realized the room was actually quite dark. The floor was made of plain old dirt, and the walls were made of bumpy clay that looked like it had been put there a long time ago.…”

This is a chain of micro-actions that don’t add pressure. We don’t learn anything new about the characters. The situation doesn’t tighten. The reader doesn’t get a problem, a risk, a cost, or a surprise. We just get movement described like the camera is obligated to record every step.

If nothing happens during the walk, the walk is just a receipt you’re stapling to the scene to add words.

Exhibit B: “information delivery”

“Are you ready for this?” Sir Barnaby asked his best friend, who was standing right there next to him. His friend gave a quick nod to show he was definitely ready, so Barnaby used his muscles to push open the big, heavy doors. He walked right into the meeting room of the Secret Cape Society in the city of Glorpville. His metal boots made a really loud clanking sound on the floor, which was made of red bricks, every single time he took a step. High up above, there was a huge chandelier with lots of lights that made his silver chest armor look very shiny and sparkly. It filled the whole room with a kind of yellow light that was pretty soft. There were also tons of weapons on the walls, like big swords, long swords, pointy axes on sticks, and shields that were all different sizes.

See the strings?

The question exists to announce “a big moment,” not because a human would ask it in that way.

“Best friend, who was standing right there next to him” is the prose equivalent of clearing your throat into the microphone.

The setting is introduced like a tour guide. The reader isn’t inside a scene, they’re on a museum audio track.

It’s information delivery. It’s handing the reader a clipboard and asking them to admire the facts.

But narrative doesn’t run on facts. It runs on pressure.

What’s missing? This entrance should do something to Barnaby. Or to the room. Or to their relationship.

Exhibit C: “dialogue from hell”

Steve blinked his eyes in total shock. The scary monster, The Party Beast, was now standing right over Brenda, who was laying flat on the ground. Long, gross strings of spit were dripping out of the beast’s mouth and off his tongue, which was also gross. Steve literally had no clue how the monster had run over to her that quickly.

“I’m going to hurt your wife and your kid and make you watch the whole thing,” the beast said in a mean voice. “I’m going to play them like they are guitars or pianos all night long, and they’re going to sing a really long, sad song about pain. It’ll be like a scary opera just for you. Then I’ll let you go so you can always remember the smells and the sounds of your family. Maybe one day I’ll find you again and finish the job.”

Steve started shaking really, really hard, almost like he was having a fit. He tried to take a deep breath to calm down, but his chest was just moving in short, fast wiggles. He couldn’t get any oxygen into his lungs at all.

“No way,” he whispered while squeezing his teeth together.

“Just take me instead. Do it to me.”

The Party Beast started laughing, and the sound was so scary it made Steve’s blood feel like it was turning into ice cubes.

“Nope! I’m not going to let you be a hero today. You have to stay right there, totally frozen, and you aren’t allowed to close your eyes or look at something else.”

It felt like there was invisible super glue holding Steve to the floor. His muscles just wouldn’t work no matter how hard he tried.

Steve felt totally useless as he watched the Party Beasts’s hand reach down toward his wife’s neck.

Stilted villain dialogue has one tell. It explains the evil instead of committing it. The first line has bite. Then the scene leaks pressure because the Party Beast starts touring us through his cruelty like he’s proud of his itinerary.

What kills it:

The villain gives a full schedule

All-night piano-guitar torture. “Maybe one day.”

The Party Beast gives Steve a Yelp review of future violence. The reader, half-bored, has time evaluate the prose. That’s the opposite of fear.The language turns abstract right when it should turn specific

Horror lives in one concrete, human detail that the reader can’t unsee. Not “Pain.” “Sad song.” “Remember.” “Finish the job.”The text labels emotions instead of causing them

If it’s scary, don’t tell me it’s scary. Make my brain do it by showing consequence. “In total shock,” “mean voice,” “so scary,” “really, really hard,” “ice cubes,” are training wheels.The hero is not panicked

“Just take me instead. Do it to me.”

In real terror, people don’t audition for nobility. They bargain badly. They choke. They lie. They promise anything.

Here’s the rule that keeps your text tense:

If the monster’s speech gives the reader time to relax, you’ve lost the scene.

Make a new resolution

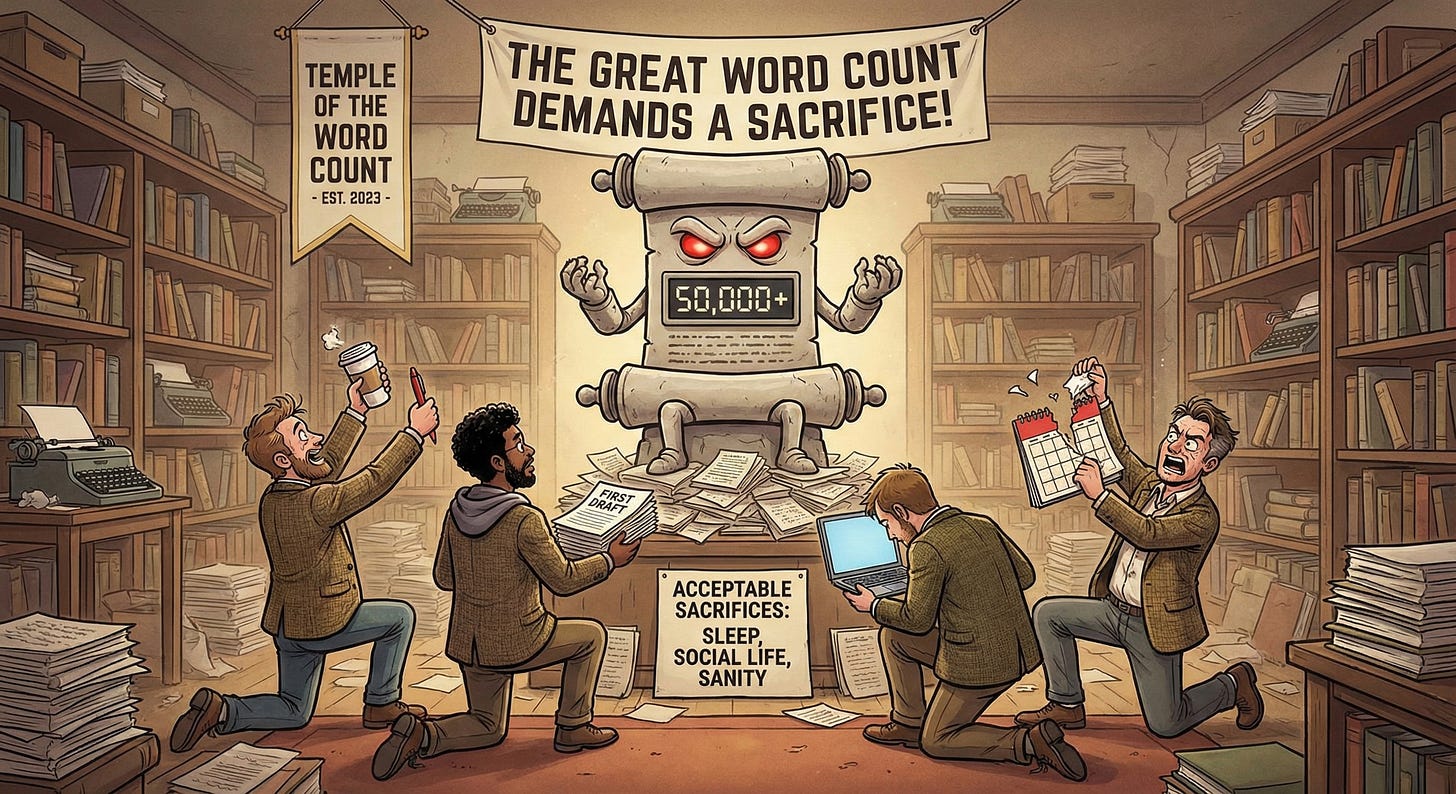

Stop feeding the Word Count God.

Write less. Make it hurt more.

Cut the travelogues.

Cut the vibes that changes nothing.

Cut the dialogue that explains instead of weaponizes.

Cut the training wheels: he felt / she realized / in total shock.

Cut anything that could vanish without leaving a bruise (except to your pride).

If you need a number to chase, chase this:

How many times did the scene change today?

Anything else is just … packaging.

The Test and the Audit

The Change Test: Underline every sentence that moves the needle. If a sentence doesn’t shift the plot, the character’s perspective, or the power dynamic, leave it plain.

The Fear Audit: Look at every paragraph you didn’t underline. Ask yourself: “What am I hiding from here?” Usually, a stagnant paragraph is a shield protecting you (or the reader) from:

The Hard Choice: A decision that can’t be taken back.

The Hard Reveal: A truth that changes everything.

The Hard Cut: Getting straight to the point.

The “Vibe” Verdict

The Pressure Statement: for every scene, complete this sentence: > “By the end of this scene, [Action/Outcome X] is no longer possible.”

If you can’t write a Pressure Statement, you don’t have a scene. You have “vibes.” Vibes don’t drive a story. If nothing becomes impossible, nothing has actually happened.

This is great advice for horror, thrillers, and action-oriented plot.

I would not apply it to cozier works like slice of life, memoirs, or certain romances. Fantasy could use some of this for its action scenes, but be allowed to use that ambience you despise for immersion in the world with very carefully sprinkled lore.

So true