This is the seventh rule in my text on Writing. The other posts are available in the Writing With Vane section. Short brief about me: I’m a writer who started writing in the late 80s and a I have few new books out. Subscribe for free below for the occasional newsletter.

Most writers don’t fail because they can’t start writing. They fail because they can’t finish.

They keep going until the speculative tension—the “what if”—loses pressure. Or they stop early, relieved, before the world actually lives or the stakes have been earned. Both mistakes feel similar while you’re making them: you’re no longer writing with authority.

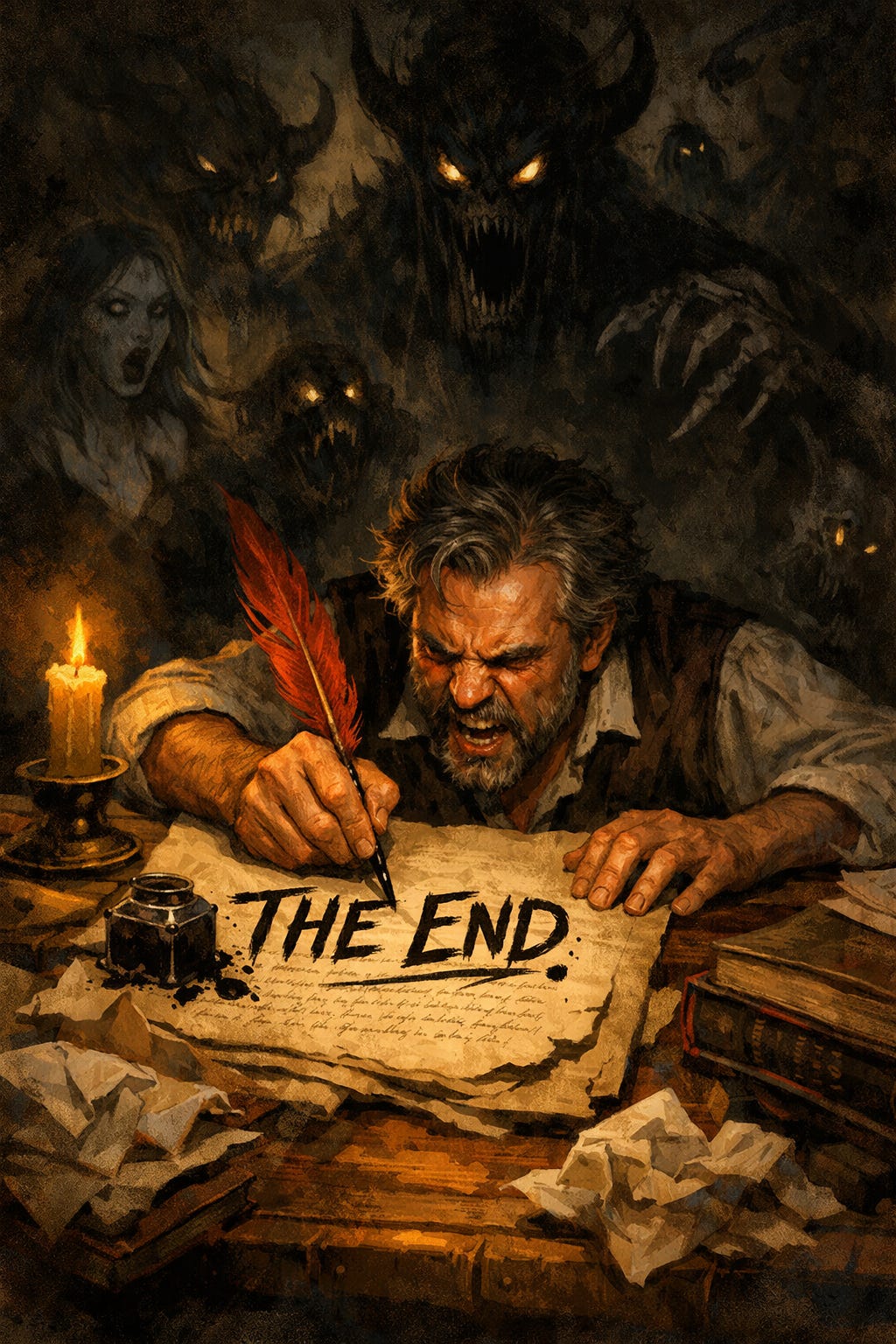

In speculative fiction, the beginning is intoxicating; it’s all possibility, potential, and the god-like power of world-building. But getting to THE END? That is a separate skill. It requires different muscles, a different mindset, and a different relationship with the work.

They keep going until the speculative tension loses pressure. Or they stop early, relieved, before the world actually lives. Both mistakes feel similar: you’re no longer writing with authority. You’re writing out of nerves.

“Done” is not a mood. “Done” is a condition. It is the moment your world-logic and your character’s truth lock together. You learn it by being honest with yourself. Not “kind.” Honest.

Two ways you miss the finish line

You Go Too Long

You keep adding to the world after the point has landed. The ending becomes a hallway of extra paragraphs that apologize for the “weirdness” of your premise by over-explaining it.

Warning lights for “too long”:

Dismantling The Mystery

You feel the urge to "make sure" the reader understands exactly how the monster works, stripping away the awe.

The Echoing Theme

You’ve already shown the "aliens are a metaphor for grief," but you spend the final chapter explaining the metaphor again through a side character.

The Apology

You feel the urge to “make sure” the reader gets it and use "In this world..." or "As everyone knows..." to justify a plot point you didn't set up well enough earlier.

When a text is too long, it feels needy. It’s a sign you’re afraid to let the reader judge the work, so you keep talking to delay the verdict.

You Stop Too Early

You quit when you’re tired, not when the text is complete. The idea is there, but it hasn’t been earned. You’ve stated a miracle or a horror, but you haven't built the structure to earn it. The reader can sense the missing work.

Warning lights for “too short”:

When the text is too short, it doesn’t feel sharp. It feels unbuilt.

The Magic Reset

The conflict is resolved by a power or technology that has no cost, no limit, and no previous mention.

The Hand-Wave

The core speculative claim (the time travel, the curse, the portal) is stated, but the consequences aren’t made believable.

The White Room

Your characters are talking, but the "speculative" element has vanished. They could be in a modern office or a Starbucks and nothing would change.

The Emergency Exit

The ending arrives like a fire alarm—abrupt and evasive—because you didn’t know how to resolve the high-concept mess you created.

The Abstract Ending

You used "cosmic energy" or "darkness" because you didn't want to do the hard work of designing a concrete, visceral consequence.

When a text is too short, it feels unbuilt. You’ve fled the scene before the “Last 20%”—the hardest part—could be finished. And guess what? When you’ve written the last 20%, everything falls into place. The beginning and middle can get the flourish it needs.

The Three Signs You’ve Arrived

Sign 1: When the World and the Story "Lock"

This is not “I like it.” This is: it clicks. The text carries. The tone matches throughout. This is the moment the Novum (your speculative element) and the Human Heart become one. The final line doesn’t beg for help because the world’s internal logic has provided the answer.

In practice, that feeling comes from alignment:

The opening promises something the text actually delivers.

The middle moves, not wanders.

The ending resolves the motion, even if it resolves into tension.

If you reread and the piece feels inevitable, you’re close.

Sign 2: When the "Knife Test" Draws Blood

You test “done” with a knife.

This can be done on a macro-level all the way to micro-level.

Remove a detail—an alien ritual, a technical explanation—anything you deem vital. Read again.

Ask one question: Did anything essential disappear?

Essential means one of three things:

Meaning: the reader no longer understands what you mean.

Proof: the reader no longer believes you.

Movement: the rhythm, transition, or logic collapses.

Did the logic collapse? (Keep it; it’s infrastructure.)

Did the wonder fade? (Keep it; it’s atmosphere.)

Did nothing change? (Cut it. It was an info-dump.) When every remaining sentence is a load-bearing pillar, you are finished. Not because it’s perfect, but because it’s necessary.

Sign 3: When the Text Carries Itself

A finished speculative text doesn’t need “scaffolding.” It doesn’t need a glossary or a final page of self-justification. If the world stands upright without you holding it, you’re done.

The sign: The story ends, but the world feels like it keeps turning. You haven't exhausted the setting; you’ve simply completed the character's journey within it. The text "stands upright" when the reader is left with a question they want to ponder, rather than a confusion they need you to clarify.

The “Last 20%” Mindset

The final push is harder because the Resistance is stronger.

To finish, you must commit to this ending and this version of the world.

You have to kill all the "theoretically better" stories you could have told to let this real one live. There will always be a gap between the masterpiece in your head and the text on the page. Finishing requires the courage to say, "This is the best version I can create right now."

A mediocre finished script teaches you more than a "perfect" unfinished one. Finishing is a muscle; you build it by typing "The End" on imperfect things.

A mini revision process that teaches you “done”

This skill takes time because it’s partly craft and partly self-discipline. You develop it by repeating a small, strict loop:

Rest the draft. Step away long enough to lose the glow of having written it.

The “Tourist” cut. Identify any paragraph that exists solely to show off your research or imagination but doesn't force a character to make a choice. Delete it.

Cut for necessity. Remove one paragraph or five sentences. Read again. Keep what hurts to lose. Delete what doesn’t.

The "Sensory" Check. If a scene feels "unbuilt," add one concrete sensory detail that is impossible in our world (the smell of ozone from a wand, the wrong-colored sun).

The Final Sound-Off:. Read the ending aloud. If it sounds like a lecture, it’s too long. If it sounds like a shrug, it’s too short.

Then you repeat, Until the three signs show up.

The exception: some texts should feel unfinished

Sometimes the correct ending is a deliberate lack of comfort. Some pieces are meant to leave the reader in unease, because unease is the point.

But listen carefully: the unease must be intentional. It has to be designed, not accidental.

A deliberate unsettled ending still shows control:

The structure is clear.

The question left open is the right question.

The reader feels challenged, not confused.

The final note feels chosen, not abandoned.

Leaving a reader in tension can be powerful. Leaving them in mess is just sloppiness.

Examples:

Franz Kafka — The Trial

A masterclass in designed unease. It doesn’t resolve because the system doesn’t resolve. You finish it feeling indicted by the universe.

Albert Camus — The Stranger

Not “unfinished” in plot terms, but philosophically it refuses comfort.

Jeff VanderMeer — Annihilation

Controlled ambiguity. It’s not “what happened?” so much as “what counts as you, after the world edits you?”

Done is a decision you earn

You don’t “feel done” by luck. You earn it by cutting, rereading, and being honest.

Stop when it sits.

Stop when you can’t cut without harm.

Stop when the text carries itself.

That’s what “finished” looks like.